Well, it isn't. And sometimes it makes you want to cry. Like yesterday, for instance, when we had to hoick out all twenty tomato plants because of late blight.

It was a bit like déja vu. We'd already had a serious attack of tomato blight in June (aka monsoon season), and in retrospect probably should have pulled up all of those plants and burnt them well before we did. But we didn't: we tried to save them. But we didn't: in the end they had to go. In went the next lot of tomato plants, in another bed. They thrived; it was a joy to watch them every day. True, some of them showed the occasional small brown patch, which we quietly removed. As all the other local organic growers do here, we gave them a treatment of Bordeaux mixture. Tomatoes started to form; we held our breath. So far, so good. Until last week, a couple of days of which were cool and a bit damp; we went to bed one night with healthy plants, and woke twelve hours later to four rows of sad horrible brown wilted scabby things. It was that fast.

If we discount my original theory that the Saints de Glace are having a laugh at my expense, I'm baffled. Our land hasn't grown vegetables for nearly 30 years. We don't grow potatoes. Our neighbours haven't got blight. We raised the plants from seed. So why? Yes, I realise it's probably not A Really Big Issue in the overall scheme of things, but it's pretty devastating when it happens. And we're going to have to think hard about how to deal with it next year.

There's an approach to growing practised here in France, originally just in viticulture but now more widely in agriculture, called 'lutte raisonée' - literally, 'reasoned struggle'. It's not organic, exactly, but those who practise it will only use any form of pesticide or fungicide treatment as an absolute last resort, having weighed up the environmental impact of treating against the overall impact of not treating. So no spraying 'just in case', and if the decision is made to treat, it will be because it's necessary to save an entire crop, and it will be done in such a way as to minimise damage to the soil and to beneficial insects. Almost all of the top wine domaines practise lutte raisonée, and I can see why. To me, sustainability has to be holistic, which means taking into account the personal and financial impact of an action as well as its impact on the Environment with a big E.

For example (and deep greens, look away now), we occasionally use slug pellets. We do so not because we don't know about or haven't thought about other methods, or because we don't care. We do so because we live and grow, here at Grillou, in an environment which can sometimes be very challenging indeed: in the middle of woodland with, in wet weather, more (and bigger) slugs and snails than I have ever seen in my life. Beer traps, eggshells, coffee grounds and all the rest simply don't cut it here: with half a hectare we can't afford nemotodes; I'm certainly not paying 30 euros for six copper rings (especially as we'd need at least 60 ...); and sorry, but staying up all night to pick the things off my plants is simply not an option. So if we're to produce any seedlings or any lettuce at all, pellets it is, sometimes.

Being green isn't the nice cuddly, fluffy little number it's often made out to be. It's about hard work, hard thinking and even harder choices. And it's not easy.

Tuesday, 26 August 2008

Thursday, 21 August 2008

Once upon a time ...

I want to tell you a story, about our village, Rimont. Are you sitting comfortably? I hope so, because you might not be afterwards.

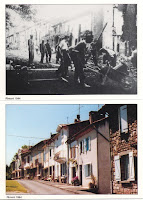

The picture above is of Rimont, taken last year. An attractive and peaceful bastide village built on a mound (le mont riant: laughing hill) in the foothills of the Pyrénées, surrounded by hills and farms. The village dates back to the thirteenth century. So, a mystery. Why do so few medieval houses remain? Here is its story.

Early in 1943, the Vichy government instituted a work scheme. Those born between 1920 and 1922 would henceforth be required to go and work in Germany to replace Germans who’d been drafted into the Wehrmacht. Unsurprisingly, many young people refused; instead they left home and hid deep in the country, in particular in the forests. Ariège (which by this time was, like the rest of the south of France, occupied by the Nazis) became a magnet for these early refugees because of its sheer wildness and isolation. Together with others - political activists, trade unionists, those who’d escaped from internment camps and Jews - they formed the first organised resisters - the maquis.

Over the next year, the three maquis groups in and around Rimont became increasingly active and organised various guerrilla actions: sabotaging factories, ambushing railways and Nazi troops as they moved through the department. Travelling the main road between Foix and St Girons became more and more hazardous for the occupiers. Things really began to hot up after the Normandy landings in June 1944; guerrilla actions were now happening every few days, and in turn both the Germans and the local French milice cracked down even harder: repression and reprisal became the official orders of the day. In Saint Girons, for example, an industrialist and prominent member of the fascist Parti Populaire Français created his own commando group, which according to one source “sows terror, tortures, plunders, burns, assassinates with impunity and often exceeds the Gestapo itself in effectiveness”.

At the little Chateau de Vignasse in the centre of Rimont lived Paul Laffont, a politician and one of Ariège’s great and good: member of parliament, senator, Secretary of State for Post, Telegraph and Telephone, President of the Conseil General (county council) … Like most radical-socialists of his day, Paul Laffont originally gave 100% support to Marshal Pétain and the Vichy government. And like most radical-socialists of his day, he remained pétainist for only a few months: unhappy at the racist and increasingly brutal collaborationist regime of the Vichy government, he decided to withdraw from political life. Refusing all the posts offered to him by Vichy, he was then ‘relieved’ of his position as president of the Conseil General. Many of his friends, such as the mayor of Rimont, suffered the same fate. Gradually, he attempted to engage in the Resistance movement – not entirely successfully as the majority of resisters found it hard to forgive his original support of collaboration. He did, however, succeed in giving a large sum of money to the local maquis. All the while, Laffont was under observation by both the German police and the French milice, some of whom apparently believed that he could be the chief instigator of the resistance that they feared yet knew little about. Early in the morning of the 13 July 1944, a Franco-German commando arrived at Laffont’s home in Rimont, seized him, took him away in a van to an unknown destination, then ransacked and vandalised his house. His close friend, Doctor Charles Labro, heard the commotion and ran towards the chateau; he too was brutally seized and taken away. Their bodies were found, separately, several days later, that of Doctor Labro very close to Grillou (now marked by a memorial). Both men had been tortured before being killed.

The price of liberation for Rimont was a high one: the village plus several farms and hamlets were burned almost in totality. 236 buildings were destroyed, including 152 houses, the schools, the Mairie, and all the village archives with it. 231 Rimontais were made homeless. Grillou survived, untouched.

As you enter the village today, you’ll see a chilling epitaph: ‘Rimont, village martyr’. The village was rebuilt afer the war, as closely as possible in style and construction to the original, and the 'village ressuscité' was inaugurated by the Minister for Reconstruction in 1950. As you walk the streets of Rimont, Saint Girons and the other local towns and villages, you’ll come time and time again across streets named after the men in these, and other, stories. The battle of Rimont may not have made the heroic war films of my childhood, but it lives on, here.

The picture above is of Rimont, taken last year. An attractive and peaceful bastide village built on a mound (le mont riant: laughing hill) in the foothills of the Pyrénées, surrounded by hills and farms. The village dates back to the thirteenth century. So, a mystery. Why do so few medieval houses remain? Here is its story.

Early in 1943, the Vichy government instituted a work scheme. Those born between 1920 and 1922 would henceforth be required to go and work in Germany to replace Germans who’d been drafted into the Wehrmacht. Unsurprisingly, many young people refused; instead they left home and hid deep in the country, in particular in the forests. Ariège (which by this time was, like the rest of the south of France, occupied by the Nazis) became a magnet for these early refugees because of its sheer wildness and isolation. Together with others - political activists, trade unionists, those who’d escaped from internment camps and Jews - they formed the first organised resisters - the maquis.

Over the next year, the three maquis groups in and around Rimont became increasingly active and organised various guerrilla actions: sabotaging factories, ambushing railways and Nazi troops as they moved through the department. Travelling the main road between Foix and St Girons became more and more hazardous for the occupiers. Things really began to hot up after the Normandy landings in June 1944; guerrilla actions were now happening every few days, and in turn both the Germans and the local French milice cracked down even harder: repression and reprisal became the official orders of the day. In Saint Girons, for example, an industrialist and prominent member of the fascist Parti Populaire Français created his own commando group, which according to one source “sows terror, tortures, plunders, burns, assassinates with impunity and often exceeds the Gestapo itself in effectiveness”.

At the little Chateau de Vignasse in the centre of Rimont lived Paul Laffont, a politician and one of Ariège’s great and good: member of parliament, senator, Secretary of State for Post, Telegraph and Telephone, President of the Conseil General (county council) … Like most radical-socialists of his day, Paul Laffont originally gave 100% support to Marshal Pétain and the Vichy government. And like most radical-socialists of his day, he remained pétainist for only a few months: unhappy at the racist and increasingly brutal collaborationist regime of the Vichy government, he decided to withdraw from political life. Refusing all the posts offered to him by Vichy, he was then ‘relieved’ of his position as president of the Conseil General. Many of his friends, such as the mayor of Rimont, suffered the same fate. Gradually, he attempted to engage in the Resistance movement – not entirely successfully as the majority of resisters found it hard to forgive his original support of collaboration. He did, however, succeed in giving a large sum of money to the local maquis. All the while, Laffont was under observation by both the German police and the French milice, some of whom apparently believed that he could be the chief instigator of the resistance that they feared yet knew little about. Early in the morning of the 13 July 1944, a Franco-German commando arrived at Laffont’s home in Rimont, seized him, took him away in a van to an unknown destination, then ransacked and vandalised his house. His close friend, Doctor Charles Labro, heard the commotion and ran towards the chateau; he too was brutally seized and taken away. Their bodies were found, separately, several days later, that of Doctor Labro very close to Grillou (now marked by a memorial). Both men had been tortured before being killed.

The battle of Rimont

Resistance was hotting up, and the Allied landings in Provence in August 1944 gave added impetus to the maquis of Ariège, which by now was playing a prominent part in the increasingly organised push towards liberation. On 20 August 1944, a long column of soldiers from the Legion of Turkestan, an adjunct to the German army made up of Central Asian prisoners from the Soviet war, was making its way from Saint Gaudens to Saint Girons; on arrival, there was fierce fighting in which the charismatic leader of one of Rimont’s maquis groups, Réné Plaisant, was killed; the maquis reluctantly decided to withdraw from the town to avoid carnage. That night was a rough one: hostages were taken, fires lit, shops and houses pillaged and women raped.

The next day, 21 August, the column set out towards Rimont – around 15 kilometres. Around 9am that morning, the local garage owner, who was on observation duty, saw it approaching. He counted 44 trucks without seeing the end of the column. Things were serious: there were at least 2000 men. The order to evacuate was given and many of Rimont’s inhabitants hid in the countryside. In the way of such things, however, the gendarmes – who were not on the best of terms with the résistants - had just received a message that a group of 15 Germans were approaching. The gendarmes went around all the houses asking those remaining not to leave but just to lock themselves in their houses. Many of the elderly preferred to sit it out at home, and complied. At the same time, the maquis managed to hold off the column until 11am, long enough for most of the population to flee, at which point they retreated, vastly outnumbered.

The German soldiers surrounded Rimont; the commander gave the order to burn the village to force a passage through it. Soon Rimont was engulfed by flames, the German and Turkestan soldiers screaming in a mad folie of rage, egged on by the French milice. The Rimontais could only flee to the surrounding hills, from where they watched helplessly as the medieval bastide village, along with everything they owned, went up in smoke. Those who lingered were attacked by German police dogs. Women were raped in their houses. All in all eleven Rimontais died in the combat, mainly elderly, one while he peeled potatoes outside his front door. Several groups of hostages were taken; the women were freed at midday, while one group of men were lined up along the wall of the local wine merchant. Realising that they were going to be shot, one of them, François Sentenac, made a break for it and escaped through the open hallway of the house behind him and through into the gardens beyond. The German soldiers gave chase, never returning. Other men were forced to lie face down in the middle of the battle until nightfall. This is how one of them described the experience:

“No idea what time it is. Not for a minute are we hungry or thirsty or cold. We feel nothing. And the battle rages around us while we serve as shields as the maquis kill opposite. And just over there, our village burns …”.

The column eventually moved through Rimont and on towards our neighbouring village of Castelnau Durban, which it occupied that night; the next day it continued its march but by that time large numbers of maquis fighters had arrived from Aude and Haute Garonne. Finally the Germans realised that they’d lost; they capitulated at Ségalas, defeated by 400 maquis.

Resistance was hotting up, and the Allied landings in Provence in August 1944 gave added impetus to the maquis of Ariège, which by now was playing a prominent part in the increasingly organised push towards liberation. On 20 August 1944, a long column of soldiers from the Legion of Turkestan, an adjunct to the German army made up of Central Asian prisoners from the Soviet war, was making its way from Saint Gaudens to Saint Girons; on arrival, there was fierce fighting in which the charismatic leader of one of Rimont’s maquis groups, Réné Plaisant, was killed; the maquis reluctantly decided to withdraw from the town to avoid carnage. That night was a rough one: hostages were taken, fires lit, shops and houses pillaged and women raped.

The next day, 21 August, the column set out towards Rimont – around 15 kilometres. Around 9am that morning, the local garage owner, who was on observation duty, saw it approaching. He counted 44 trucks without seeing the end of the column. Things were serious: there were at least 2000 men. The order to evacuate was given and many of Rimont’s inhabitants hid in the countryside. In the way of such things, however, the gendarmes – who were not on the best of terms with the résistants - had just received a message that a group of 15 Germans were approaching. The gendarmes went around all the houses asking those remaining not to leave but just to lock themselves in their houses. Many of the elderly preferred to sit it out at home, and complied. At the same time, the maquis managed to hold off the column until 11am, long enough for most of the population to flee, at which point they retreated, vastly outnumbered.

The German soldiers surrounded Rimont; the commander gave the order to burn the village to force a passage through it. Soon Rimont was engulfed by flames, the German and Turkestan soldiers screaming in a mad folie of rage, egged on by the French milice. The Rimontais could only flee to the surrounding hills, from where they watched helplessly as the medieval bastide village, along with everything they owned, went up in smoke. Those who lingered were attacked by German police dogs. Women were raped in their houses. All in all eleven Rimontais died in the combat, mainly elderly, one while he peeled potatoes outside his front door. Several groups of hostages were taken; the women were freed at midday, while one group of men were lined up along the wall of the local wine merchant. Realising that they were going to be shot, one of them, François Sentenac, made a break for it and escaped through the open hallway of the house behind him and through into the gardens beyond. The German soldiers gave chase, never returning. Other men were forced to lie face down in the middle of the battle until nightfall. This is how one of them described the experience:

“No idea what time it is. Not for a minute are we hungry or thirsty or cold. We feel nothing. And the battle rages around us while we serve as shields as the maquis kill opposite. And just over there, our village burns …”.

The column eventually moved through Rimont and on towards our neighbouring village of Castelnau Durban, which it occupied that night; the next day it continued its march but by that time large numbers of maquis fighters had arrived from Aude and Haute Garonne. Finally the Germans realised that they’d lost; they capitulated at Ségalas, defeated by 400 maquis.

The battle of Rimont, which took place exactly sixty-four years ago today, put an end to the Occupation in Ariège. Remarkably, the department was liberated entirely through civilian fighting – no regular armed forces were involved. But in France, the Second World War had become not just a fight against the Germans, but also one against the Vichy government. Those who had actively helped Vichy, whether by helping the Milice, denouncing the maquis or organising deportations, were arrested and tried: immediately following the liberation, France was swept by a wave of executions, public humiliations, assaults and detentions of suspected collaborators, known as the épuration sauvage (lit: wild purge); many dozens of people were shot in Ariège alone.

The price of liberation for Rimont was a high one: the village plus several farms and hamlets were burned almost in totality. 236 buildings were destroyed, including 152 houses, the schools, the Mairie, and all the village archives with it. 231 Rimontais were made homeless. Grillou survived, untouched.

As you enter the village today, you’ll see a chilling epitaph: ‘Rimont, village martyr’. The village was rebuilt afer the war, as closely as possible in style and construction to the original, and the 'village ressuscité' was inaugurated by the Minister for Reconstruction in 1950. As you walk the streets of Rimont, Saint Girons and the other local towns and villages, you’ll come time and time again across streets named after the men in these, and other, stories. The battle of Rimont may not have made the heroic war films of my childhood, but it lives on, here.

Note: my thanks to two French sites for the detail in this account: www.histariege.com, and this one. As far as I know, this is the first account in English of the battle of Rimont.

Monday, 11 August 2008

Meet the neighbours

In summer, as you travel from Grillou towards Le Mas d'Azil (a small bastide some 15 minutes from here with a good market on Wednesdays, and the only place I know where you actually drive through a cave), there comes a point where you blink hard and shake your head, wondering if you drank too much the night before. Because standing or sitting beside the road in the tiny hamlet of La Saret are a bunch of people who look as though they've come straight out of the nineteenth century:

Baffled, you park, and set off to find out what you think you're seeing ...

... and discover that you've encountered Les Sarettoises.

This is how they describe themselves:

Their expressions and their stances are so lifelike that you just can't help talking to them ...

If you happen to be travelling the other way, towards Foix, however, you might just be quick enough to encounter these people on the side of the road:

Just another couple of Ariège's quirks ...

Baffled, you park, and set off to find out what you think you're seeing ...

... and discover that you've encountered Les Sarettoises.

This is how they describe themselves:

"Born from the imagination and the fairy fingers of Betty, we have settled here since 2005, when the sunny days come we live outside in our village of Saret. Each year we are more and more, we exist only for your smile or your photograph and to wish you with our heartwarming welcome to our beautiful mountain ariégoises. Thus leave a small word in the guest book as it will warm our hearts when the beautiful days have gone, for we will be closed in a barn safe and dry and in the warm".

Their expressions and their stances are so lifelike that you just can't help talking to them ...

If you happen to be travelling the other way, towards Foix, however, you might just be quick enough to encounter these people on the side of the road:

Just another couple of Ariège's quirks ...

Wednesday, 6 August 2008

Not waving but drowning

Plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums plums ...

Thirty-five kilos and counting ...

Thirty-five kilos and counting ...

Monday, 4 August 2008

Ariège en fête

Since early July, Ariège has been en fête in a big way, and will be until la rentrée on 2 September, when the streets will empty, the pace will slacken and life becomes (a little) more serious again. When I was a mere traveller in France, I always wondered at and about the national obsession with the summer: why, for instance, does the entire world and his poodle want to travel south for their holidays on exactly the same day every year, causing traffic jams of over 800km on the autoroute system? Why are just two months of the year so full of life and activity, while in much of rural France - not here, admittedly - you'd be forgiven for thinking that the population had been evacuated during the remaining ten? Where do French villagers go in the winter? What's the big deal about la rentrée anyway and why does everybody, from plumbers to politicians, go on about it?

I confess that throughout my whole working life in England, I avoided school holidays like the plague, taking my own summer breaks in June or September when anyone under 16 was safely incarcerated in school and out of my way, and staying home to do the cleaning or something equally exciting - and crowd-free - on Bank Holidays. Apart from vacations spent working here as a student (which don't count, because I was - er - working), the first summer I'd spent in France was last year ... and that was in a village near Castelnaudary, which I do have to tell you is not one of my favourite places - though that's another story. To be honest, it was a bit of a culture shock, and at first we took our Anglo-Saxon view that July and August were to be strenuously avoided at all costs. But the summer sense of joie de vivre and what-the-hell-let's-have-a-good-time soon crept up on us, and before long we were out there fêting with the best of them, although we did give the 'pig's leg roast and piano disco' in the village where we lived then (population 76, mostly older than that) a miss. And it's true - there is a kind of magic in the air in the summer months here. It's as if you enter a kind of time warp - a different culture, almost a different universe, in which the so-called 'normal' rules of engagement with life are suspended. It becomes a perfectly normal thing, for example, to find yourself sitting in a café at 2.30am after an open air concert alongside what feels like an entire townful of other people, of all ages, from 1 to 101, all doing the same thing, or promenading, or just standing talking to friends. Or sharing a long table with twenty-plus strangers at lunchtime. Or staying at Lac Mondély until after midnight just because it's a beautiful night and the moon is full.

Over the last two weeks we have, amongst other things:

... danced ourselves half to death at Terre de Couleurs, where I haven't smelt quite so much patchouli and dope since the seventies. Toumani Diabaté was fantastic but so were the other bands, especially Anakronic Electro Orkestra (sic), who are from Toulouse and play new wave Jewish music (known, I can now reveal, as new electro klezmer. But you already knew that, didn't you?). And watched a seriously awesome pyrotechnic show:

... danced ourselves slightly less than half to death (bodies getting back into it now!) at the Louis Bertignac concert at St Girons. Who? No, I didn't know either until I read about him in our regional rag. He's a rock guitarist, France's answer to Keith Richards and something of a cult figure here, having been around pretty continuously since the seventies and now playing as part of the group Power Trio. For me, a (middle-) aging hippy of the same era, it was pure bliss - Stones meets Led Zep meets Hendrix. They played, without a breather, for three hours, and I turned back into a groupie. I haven't been to such a loud and intense rock gig since the days of Hammersmith Odeon. I'm not sure that St G has ever heard anything quite like it either ...

... discovered an exciting new African band, Les Espoirs de Coronthie, at the festival Ingénieuse Afrique in Foix. Great music, a bit Mali, a bit Senegal but not quite either (they're from Guinea), great sound and great energy.

As does the whole three day festival. We had huge fun processing round the town with some drummers and dancers:

... and (now for something completely different) travelled back in time at Autrefois les Couserans at St Girons, which for the last 15 years has been putting on a major celebration of the heritage and the 'olden days' of life in our local valleys. It was heaving! Apparently it attracts around 25,000 visitors every year; we were there yesterday, and I think all the 24,998 others were as well, enjoying / enduring temperatures well into the thirties. It's a really good 'do': a huge procession lasting nearly two hours in which 600 people, 50 vintage tractors and more animals than I can count take part, endless stalls and demonstrations, even a farmyard set up in one of the local squares. At lunchtime every square centimetre of space is taken over by tables and chairs as restaurants and cafés both temporary and permanent face up to the daunting task of feeding the twenty-five thousand, all between the sacred hours of twelve and two, naturally. John (bless) got very excited by the (working) steam-driven threshing machine that apparently looked just like the one that used to turn up on his family farm when he were a lad; I got excited by the food market, where I got into a somewhat heated discussion with a militant Ariégeois about bears. Not perhaps the most sensible thing to do, given that the reintroduction of bears into Ariège-Pyrénées a few years ago is probably just about the most contentious issue round here and raises more steam amongst sheep farmers than the afore-mentioned steam engine ...

Here's a glimpse of St Girons (I took this yesterday. Not bad weather, huh?):

... and a part of the procession:

The costumes are for real (including the clogs), and are a feature of the valley of Bethmale. These days they're only worn on ceremonial occasions though. There's still a clog-making workshop in the valley.

This is for John - the famous threshing machine:

Phew. Time for a break. So after our festival fest (can I say that?), something approaching normal life will be returning to Grillou this week - shutters will be sanded, the potager hoed, kitchen cupboard doors stripped and painted, and thousands of kilos of plums (okay, so I exaggerate. But only slightly) will be picked, bottled, jammed, crumbled, compôted and given away. Allez ....

I confess that throughout my whole working life in England, I avoided school holidays like the plague, taking my own summer breaks in June or September when anyone under 16 was safely incarcerated in school and out of my way, and staying home to do the cleaning or something equally exciting - and crowd-free - on Bank Holidays. Apart from vacations spent working here as a student (which don't count, because I was - er - working), the first summer I'd spent in France was last year ... and that was in a village near Castelnaudary, which I do have to tell you is not one of my favourite places - though that's another story. To be honest, it was a bit of a culture shock, and at first we took our Anglo-Saxon view that July and August were to be strenuously avoided at all costs. But the summer sense of joie de vivre and what-the-hell-let's-have-a-good-time soon crept up on us, and before long we were out there fêting with the best of them, although we did give the 'pig's leg roast and piano disco' in the village where we lived then (population 76, mostly older than that) a miss. And it's true - there is a kind of magic in the air in the summer months here. It's as if you enter a kind of time warp - a different culture, almost a different universe, in which the so-called 'normal' rules of engagement with life are suspended. It becomes a perfectly normal thing, for example, to find yourself sitting in a café at 2.30am after an open air concert alongside what feels like an entire townful of other people, of all ages, from 1 to 101, all doing the same thing, or promenading, or just standing talking to friends. Or sharing a long table with twenty-plus strangers at lunchtime. Or staying at Lac Mondély until after midnight just because it's a beautiful night and the moon is full.

Over the last two weeks we have, amongst other things:

... danced ourselves half to death at Terre de Couleurs, where I haven't smelt quite so much patchouli and dope since the seventies. Toumani Diabaté was fantastic but so were the other bands, especially Anakronic Electro Orkestra (sic), who are from Toulouse and play new wave Jewish music (known, I can now reveal, as new electro klezmer. But you already knew that, didn't you?). And watched a seriously awesome pyrotechnic show:

... danced ourselves slightly less than half to death (bodies getting back into it now!) at the Louis Bertignac concert at St Girons. Who? No, I didn't know either until I read about him in our regional rag. He's a rock guitarist, France's answer to Keith Richards and something of a cult figure here, having been around pretty continuously since the seventies and now playing as part of the group Power Trio. For me, a (middle-) aging hippy of the same era, it was pure bliss - Stones meets Led Zep meets Hendrix. They played, without a breather, for three hours, and I turned back into a groupie. I haven't been to such a loud and intense rock gig since the days of Hammersmith Odeon. I'm not sure that St G has ever heard anything quite like it either ...

... discovered an exciting new African band, Les Espoirs de Coronthie, at the festival Ingénieuse Afrique in Foix. Great music, a bit Mali, a bit Senegal but not quite either (they're from Guinea), great sound and great energy.

As does the whole three day festival. We had huge fun processing round the town with some drummers and dancers:

... and (now for something completely different) travelled back in time at Autrefois les Couserans at St Girons, which for the last 15 years has been putting on a major celebration of the heritage and the 'olden days' of life in our local valleys. It was heaving! Apparently it attracts around 25,000 visitors every year; we were there yesterday, and I think all the 24,998 others were as well, enjoying / enduring temperatures well into the thirties. It's a really good 'do': a huge procession lasting nearly two hours in which 600 people, 50 vintage tractors and more animals than I can count take part, endless stalls and demonstrations, even a farmyard set up in one of the local squares. At lunchtime every square centimetre of space is taken over by tables and chairs as restaurants and cafés both temporary and permanent face up to the daunting task of feeding the twenty-five thousand, all between the sacred hours of twelve and two, naturally. John (bless) got very excited by the (working) steam-driven threshing machine that apparently looked just like the one that used to turn up on his family farm when he were a lad; I got excited by the food market, where I got into a somewhat heated discussion with a militant Ariégeois about bears. Not perhaps the most sensible thing to do, given that the reintroduction of bears into Ariège-Pyrénées a few years ago is probably just about the most contentious issue round here and raises more steam amongst sheep farmers than the afore-mentioned steam engine ...

Here's a glimpse of St Girons (I took this yesterday. Not bad weather, huh?):

... and a part of the procession:

The costumes are for real (including the clogs), and are a feature of the valley of Bethmale. These days they're only worn on ceremonial occasions though. There's still a clog-making workshop in the valley.

This is for John - the famous threshing machine:

Phew. Time for a break. So after our festival fest (can I say that?), something approaching normal life will be returning to Grillou this week - shutters will be sanded, the potager hoed, kitchen cupboard doors stripped and painted, and thousands of kilos of plums (okay, so I exaggerate. But only slightly) will be picked, bottled, jammed, crumbled, compôted and given away. Allez ....

Labels:

Ariège,

festivals,

food,

French life,

St Girons,

world music

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)