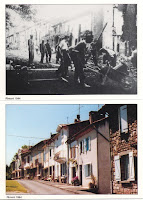

The picture above is of Rimont, taken last year. An attractive and peaceful bastide village built on a mound (le mont riant: laughing hill) in the foothills of the Pyrénées, surrounded by hills and farms. The village dates back to the thirteenth century. So, a mystery. Why do so few medieval houses remain? Here is its story.

Early in 1943, the Vichy government instituted a work scheme. Those born between 1920 and 1922 would henceforth be required to go and work in Germany to replace Germans who’d been drafted into the Wehrmacht. Unsurprisingly, many young people refused; instead they left home and hid deep in the country, in particular in the forests. Ariège (which by this time was, like the rest of the south of France, occupied by the Nazis) became a magnet for these early refugees because of its sheer wildness and isolation. Together with others - political activists, trade unionists, those who’d escaped from internment camps and Jews - they formed the first organised resisters - the maquis.

Over the next year, the three maquis groups in and around Rimont became increasingly active and organised various guerrilla actions: sabotaging factories, ambushing railways and Nazi troops as they moved through the department. Travelling the main road between Foix and St Girons became more and more hazardous for the occupiers. Things really began to hot up after the Normandy landings in June 1944; guerrilla actions were now happening every few days, and in turn both the Germans and the local French milice cracked down even harder: repression and reprisal became the official orders of the day. In Saint Girons, for example, an industrialist and prominent member of the fascist Parti Populaire Français created his own commando group, which according to one source “sows terror, tortures, plunders, burns, assassinates with impunity and often exceeds the Gestapo itself in effectiveness”.

At the little Chateau de Vignasse in the centre of Rimont lived Paul Laffont, a politician and one of Ariège’s great and good: member of parliament, senator, Secretary of State for Post, Telegraph and Telephone, President of the Conseil General (county council) … Like most radical-socialists of his day, Paul Laffont originally gave 100% support to Marshal Pétain and the Vichy government. And like most radical-socialists of his day, he remained pétainist for only a few months: unhappy at the racist and increasingly brutal collaborationist regime of the Vichy government, he decided to withdraw from political life. Refusing all the posts offered to him by Vichy, he was then ‘relieved’ of his position as president of the Conseil General. Many of his friends, such as the mayor of Rimont, suffered the same fate. Gradually, he attempted to engage in the Resistance movement – not entirely successfully as the majority of resisters found it hard to forgive his original support of collaboration. He did, however, succeed in giving a large sum of money to the local maquis. All the while, Laffont was under observation by both the German police and the French milice, some of whom apparently believed that he could be the chief instigator of the resistance that they feared yet knew little about. Early in the morning of the 13 July 1944, a Franco-German commando arrived at Laffont’s home in Rimont, seized him, took him away in a van to an unknown destination, then ransacked and vandalised his house. His close friend, Doctor Charles Labro, heard the commotion and ran towards the chateau; he too was brutally seized and taken away. Their bodies were found, separately, several days later, that of Doctor Labro very close to Grillou (now marked by a memorial). Both men had been tortured before being killed.

The battle of Rimont

Resistance was hotting up, and the Allied landings in Provence in August 1944 gave added impetus to the maquis of Ariège, which by now was playing a prominent part in the increasingly organised push towards liberation. On 20 August 1944, a long column of soldiers from the Legion of Turkestan, an adjunct to the German army made up of Central Asian prisoners from the Soviet war, was making its way from Saint Gaudens to Saint Girons; on arrival, there was fierce fighting in which the charismatic leader of one of Rimont’s maquis groups, Réné Plaisant, was killed; the maquis reluctantly decided to withdraw from the town to avoid carnage. That night was a rough one: hostages were taken, fires lit, shops and houses pillaged and women raped.

The next day, 21 August, the column set out towards Rimont – around 15 kilometres. Around 9am that morning, the local garage owner, who was on observation duty, saw it approaching. He counted 44 trucks without seeing the end of the column. Things were serious: there were at least 2000 men. The order to evacuate was given and many of Rimont’s inhabitants hid in the countryside. In the way of such things, however, the gendarmes – who were not on the best of terms with the résistants - had just received a message that a group of 15 Germans were approaching. The gendarmes went around all the houses asking those remaining not to leave but just to lock themselves in their houses. Many of the elderly preferred to sit it out at home, and complied. At the same time, the maquis managed to hold off the column until 11am, long enough for most of the population to flee, at which point they retreated, vastly outnumbered.

The German soldiers surrounded Rimont; the commander gave the order to burn the village to force a passage through it. Soon Rimont was engulfed by flames, the German and Turkestan soldiers screaming in a mad folie of rage, egged on by the French milice. The Rimontais could only flee to the surrounding hills, from where they watched helplessly as the medieval bastide village, along with everything they owned, went up in smoke. Those who lingered were attacked by German police dogs. Women were raped in their houses. All in all eleven Rimontais died in the combat, mainly elderly, one while he peeled potatoes outside his front door. Several groups of hostages were taken; the women were freed at midday, while one group of men were lined up along the wall of the local wine merchant. Realising that they were going to be shot, one of them, François Sentenac, made a break for it and escaped through the open hallway of the house behind him and through into the gardens beyond. The German soldiers gave chase, never returning. Other men were forced to lie face down in the middle of the battle until nightfall. This is how one of them described the experience:

“No idea what time it is. Not for a minute are we hungry or thirsty or cold. We feel nothing. And the battle rages around us while we serve as shields as the maquis kill opposite. And just over there, our village burns …”.

The column eventually moved through Rimont and on towards our neighbouring village of Castelnau Durban, which it occupied that night; the next day it continued its march but by that time large numbers of maquis fighters had arrived from Aude and Haute Garonne. Finally the Germans realised that they’d lost; they capitulated at Ségalas, defeated by 400 maquis.

Resistance was hotting up, and the Allied landings in Provence in August 1944 gave added impetus to the maquis of Ariège, which by now was playing a prominent part in the increasingly organised push towards liberation. On 20 August 1944, a long column of soldiers from the Legion of Turkestan, an adjunct to the German army made up of Central Asian prisoners from the Soviet war, was making its way from Saint Gaudens to Saint Girons; on arrival, there was fierce fighting in which the charismatic leader of one of Rimont’s maquis groups, Réné Plaisant, was killed; the maquis reluctantly decided to withdraw from the town to avoid carnage. That night was a rough one: hostages were taken, fires lit, shops and houses pillaged and women raped.

The next day, 21 August, the column set out towards Rimont – around 15 kilometres. Around 9am that morning, the local garage owner, who was on observation duty, saw it approaching. He counted 44 trucks without seeing the end of the column. Things were serious: there were at least 2000 men. The order to evacuate was given and many of Rimont’s inhabitants hid in the countryside. In the way of such things, however, the gendarmes – who were not on the best of terms with the résistants - had just received a message that a group of 15 Germans were approaching. The gendarmes went around all the houses asking those remaining not to leave but just to lock themselves in their houses. Many of the elderly preferred to sit it out at home, and complied. At the same time, the maquis managed to hold off the column until 11am, long enough for most of the population to flee, at which point they retreated, vastly outnumbered.

The German soldiers surrounded Rimont; the commander gave the order to burn the village to force a passage through it. Soon Rimont was engulfed by flames, the German and Turkestan soldiers screaming in a mad folie of rage, egged on by the French milice. The Rimontais could only flee to the surrounding hills, from where they watched helplessly as the medieval bastide village, along with everything they owned, went up in smoke. Those who lingered were attacked by German police dogs. Women were raped in their houses. All in all eleven Rimontais died in the combat, mainly elderly, one while he peeled potatoes outside his front door. Several groups of hostages were taken; the women were freed at midday, while one group of men were lined up along the wall of the local wine merchant. Realising that they were going to be shot, one of them, François Sentenac, made a break for it and escaped through the open hallway of the house behind him and through into the gardens beyond. The German soldiers gave chase, never returning. Other men were forced to lie face down in the middle of the battle until nightfall. This is how one of them described the experience:

“No idea what time it is. Not for a minute are we hungry or thirsty or cold. We feel nothing. And the battle rages around us while we serve as shields as the maquis kill opposite. And just over there, our village burns …”.

The column eventually moved through Rimont and on towards our neighbouring village of Castelnau Durban, which it occupied that night; the next day it continued its march but by that time large numbers of maquis fighters had arrived from Aude and Haute Garonne. Finally the Germans realised that they’d lost; they capitulated at Ségalas, defeated by 400 maquis.

The battle of Rimont, which took place exactly sixty-four years ago today, put an end to the Occupation in Ariège. Remarkably, the department was liberated entirely through civilian fighting – no regular armed forces were involved. But in France, the Second World War had become not just a fight against the Germans, but also one against the Vichy government. Those who had actively helped Vichy, whether by helping the Milice, denouncing the maquis or organising deportations, were arrested and tried: immediately following the liberation, France was swept by a wave of executions, public humiliations, assaults and detentions of suspected collaborators, known as the épuration sauvage (lit: wild purge); many dozens of people were shot in Ariège alone.

The price of liberation for Rimont was a high one: the village plus several farms and hamlets were burned almost in totality. 236 buildings were destroyed, including 152 houses, the schools, the Mairie, and all the village archives with it. 231 Rimontais were made homeless. Grillou survived, untouched.

As you enter the village today, you’ll see a chilling epitaph: ‘Rimont, village martyr’. The village was rebuilt afer the war, as closely as possible in style and construction to the original, and the 'village ressuscité' was inaugurated by the Minister for Reconstruction in 1950. As you walk the streets of Rimont, Saint Girons and the other local towns and villages, you’ll come time and time again across streets named after the men in these, and other, stories. The battle of Rimont may not have made the heroic war films of my childhood, but it lives on, here.

Note: my thanks to two French sites for the detail in this account: www.histariege.com, and this one. As far as I know, this is the first account in English of the battle of Rimont.

No comments:

Post a Comment